How to get a copy of your income tax return

How to get a copy of your income tax return

If you need a copy of your federal income tax return for any reason, you can request one for free from the Internal Revenue Service. The IRS Order A Transcript service can provide you with two types of basic tax transcripts:

- Tax Return Transcript – Your Tax Return Transcript includes can copies of your 1040 and most of the add-on schedules filed with that year’s tax return. You should request a tax return transcript if you need a full copy of your tax documentation, which may be necessary if you lose your records or need to provide a copy of your tax return to a third party like a government agency or your mortgage company.

- Tax Account Receipt – The IRS can also provide you with a Tax Account Receipt, which is a simple document including basic information about your tax account like your adjusted gross income and taxable income. This transcript can be useful for applications that require your tax status, like the Department of Education’s FAFSA application.

You can request a transcript or a receipt for the current tax year, or for any of the last three tax years. There is no fee for either a transcript or a receipt. This article will show you, step by step, how to order a Tax Account Receipt. Ordering a Tax Return Transcript follows most of the same steps.

CONTENTS

- Request transcripts online

- Request transcripts by phone

- Request transcripts through the mail

- Example tax account transcript

REQUEST DOCUMENTS ONLINE

- Visit the official IRS Web site at www.irs.gov

- In the Tools section of the homepage, click “Order a Return or Account Transcript”

- Chose item #3, “Order a Transcript”

- Enter your Social Security Number, date of birth, street address, and zip code. If you are requesting a jointly filed return, you will need to enter the information of the primary tax filer here

- Click “Continue”

- In the Type of Transcript field, select “Account Transcript” or “Tax Return Transcript” and in the Tax Year field, select “2012” or the year you would like to request

- If the information you submitted is valid, you can expect to receive a paper copy of your requested transcript within 5-10 days

REQUEST DOCUMENTS OVER THE TELEPHONE

- Call the IRS document hotline at 1-800-908-9946

- Follow the automated prompts and enter the SSN of the primary filer, your address as on file with the IRS, and any additional information requested

- Select “Option 4” if you want to request an IRS Tax Account Transcript and then enter “2012” (or the tax return year you need)

- If the information you submitted is valid, you can expect to receive a paper copy of your requested transcript within 5-10 days

REQUEST DOCUMENTS USING IRS FORM 4506-T

- If you need to request an account transcript, use IRS Form 4506-T. Otherwise, use IRS Form 4506T-EZ

- Download 4506T-EZ at http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/f4506tez.pdf

- Complete lines 1-4, following the instructions on page 2 of the form, with your personal information.

- Line 5 allows you to have your IRS Tax Account Transcript or Tax Return Transcript mailed directly to a third party by the IRS (this option is not available online and over the phone)

- On Line 6 of Form 4506-T, enter the tax forms you need a copy of (ex. “1040”)

- Choose either Box A (Tax Return Transcript) or Box B (Account Transcript)

- On Line 9 of Form 4506-T, enter the year for which you are requesting your transcript

- Sign and date the form and enter your telephone number. Only one signature is required for a joint return.

- Mail or fax the completed IRS Form 4506-T to the appropriate location provided on page 2 of Form 4506-.

- If the information you submitted is valid, you can expect to receive a paper copy of your requested transcript within 30 days. If the information included on the form is invalid, the IRS will notify you

EXAMPLE TAX ACCOUNT TRANSCRIPT

Tax return transcripts are commonly used for proof of income and proof of tax status. Below is an example of a certified IRS tax return receipt.

How can we improve this page? We value your comments and suggestions!

How can we improve this page? We value your comments and suggestions! Send Instant Feedback About This Page

How to calculate your federal income tax refund

How to calculate your federal income tax refund

For many Americans, tax season can bring about a windfall in the form of a Federal income tax refund check. You will receive a refund check if and only if you paid more then your total tax debt over the course of the year through tax witholding. This article will teach you how to calculate your expected tax refund, and how to ensure that your refund check reaches you successfully.

Calculating Your Total Tax and Total Payments

The size of your federal tax refund depends on two things – your total tax owed and your total tax witholding.

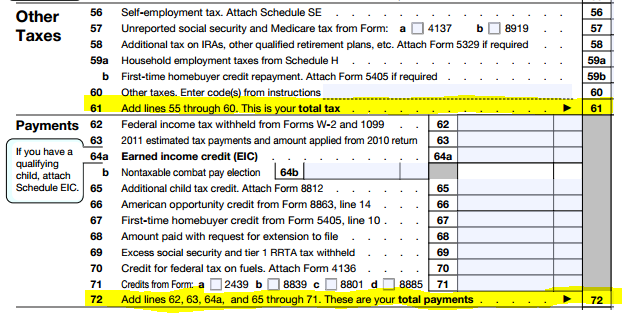

- Calculate your total tax (including all deductions, adjustments, and other taxes) on line 61 of your 1040 form. This is the amount you owe.

- Calculate your total tax payments on line 72. Tax payments include all income tax withheld by your employer on line 62 (check your W-2 or 1099 forms), estimated tax payments on line 63, and any tax credits you may qualify for. The total on line 72 is your total tax paid.

Calculating Your Income Tax Refund

Your tax refund is simply the difference between the amount you paid and the amount you owe. If you paid too much, you have several options for your refund.

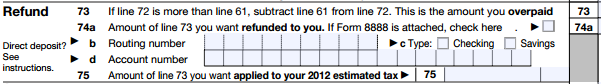

- If your total payments on line 72 are greater then your total tax owed on line 62, write the difference in the refund box on line 73.

- In lines 74 and 75, you can choose to have your refund paid to you (as a check or through direct deposit) or applied directly to next year’s taxes (useful if you have to pay estimated taxes).

Getting Your Tax Refund Quickly

Now that you’ve calculated your refund, there are several steps you can take to ensure you receive it in a timely manner.

- eFile Your Tax Return – The IRS has to process millions of tax returns every year – if you eFile, they will be able to process your return (and your refund) much more quickly. eFiled returns will receive refunds in as little as 1-3 weeks, while paper returns can take up to 6 weeks to be processed.

- Request Direct Deposit – Requesting that your refund be direct deposited instead of requesting a check can also speed up your refund process by up to a week. Direct deposit is fast and secure, and you can choose up to 3 separate accounts (including checking, savings, and retirement accounts) to receive your refund. You can request direct deposit on line 74 of your 1040.

If you eFile your tax return, you can expect to receive your refund within 10-21 days.

Checking Your Refund Status

Starting 72 hours after you eFile (or 4 weeks after you mail a paper return), you can check on your refund’s status through the IRS’ “Where’s My Refund?” system. Â Collect the following information before making your refund inquiry:

- Your Social Security Number

- Your current filing status

- The dollar amount of the refund you requested (from line 73 of your 1040)

With this information in hand, you can check the status of your refund either online or over the phone by calling the IRS Refund Hotline at  1-800–829–1954 or by logging onto the IRS Where’s My Refund website.

Solving Problems With Your Refund

If you received an incorrect refund amount, your refund was never issued , or your refund check was lost or stolen, contact the IRS immediately at 1-800-829-1040Â and they will be able to reissue your refund as necessary.

Getting Your State Income Tax Refund

If your state collects income tax, you must apply for a refund on your state income tax return, and you will receive a separate refund payment. Most states also provide an easy-to-use refund status portal – see your state’s income tax information page for more details.

How can we improve this page? We value your comments and suggestions!

How can we improve this page? We value your comments and suggestions! Send Instant Feedback About This Page

Introduction to marginal income tax brackets

Introduction to marginal income tax brackets

One of the most common misunderstandings encountered when dealing with income taxes is the concept of marginal tax brackets, and how they are used to calculate your income tax.

Marginal tax brackets are a progressive tax bracket system, which means that the effective tax rate increases as taxable income increases. Marginal tax brackets are used to calculate your federal income tax, as well as state income taxes in most states that collect an income tax. In addition to personal income taxes, marginal tax brackets are also used when calculating federal and state corporate income taxes.

In the media and everyday conversation, you may often hear references to somebody’s “tax bracket” – for example, “Most full-time employees are in the 25% tax bracket”. This language can help create the false impression that individuals “in the 25% tax bracket” actually pay a full 25% of their income in taxes. This is not true, as we will soon see. Due to the nature of marginal income tax brackets, the actual amount of tax dollars paid by an individual in the top half of the 25% tax bracket is closer to 18% of their total income [1].

A marginal income tax means that the actual tax collected on each dollar you earn depends on the total amount you have earned between the first day of the tax year and the moment you earned that dollar.

For example, let’s consider a simplified version of the 2012 federal income tax brackets: [2].

| Tax Bracket | Marginal Tax Rate |

| $0-$10,000 | 10% |

| $10,000-$35,000 | 15% |

| $35,000-$80,000 | 25% |

| $80,000-$170,000 | 28% |

| $170,000-$370,000 | 33% |

| $370,000+ | 35% |

Let’s say you earn a salary of $60,000 a year, or $5,000 per month. Starting on January 1st (the beginning of the most commonly used tax year), you have earned a total of $0. Like everyone else, you start in the 10% tax bracket, which covers earnings from $0-$10,000. Therefore, you will owe 10 cents per dollar in income tax for the first dollar you earn – and for every dollar you earn up to the $10,000 cap.

On January 31st, you receive your $5,000 monthly paycheck. You have earned a total of $5,000 since January 1st, and all of the $5,000 you earned falls below the $10,000 cap for the 10% tax bracket. Therefore, you owe a total of $5,000 x 10% = $500 in federal income tax for your January earnings.

In February, you earn another $5,000. This is also included entirely in the $0-$10,000 tax bracket, so you also owe a total of 10%, or $500, of your February earnings in income tax. So far, you’ve earned a total of $10,000 since January 1st and have paid 10%, or $1,000, of your total earnings in federal income tax.

Now, because you’ve earned a total of $10,000 so far through February, you’ve reached the cap of the first tax bracket. The next dollar you make, the $10,001th dollar, will be included in the second  tax bracket – $10,000-$35,000. In this tax bracket you will pay 15%, or 15 cents per dollar, in federal income tax. When you receive your $5,000 paycheck at the end of March, you will owe 15%, or $750, in taxes.

Now, at the end of March, you have earned a total of $15,000 in wages and paid a total of $1,750 in income tax. This includes 10% of your January earnings, 10% of your February earnings, and 15% of your March earnings. You’re currently earning in the 15% tax bracket, but if we average the effective tax rate you paid on each dollar we find that you have only paid a total of 11.67% of your total income in taxes [3]. This is the nature of a progressive tax bracket system.

Here’s how the complete yearly tax breakdown looks for our example, for all $60,000 in wages earned from January 1st to December 31st. Wages are broken down into their applicable tax brackets, including total dollars earned and total tax paid in each bracket.

| Dollars Earned | Tax Bracket | Tax Rate | Tax Paid |

| $10,000 | $0-$10,000 | 10% | $1,000 |

| $25,000 | $10,000-$35,000 | 15% | $3,750 |

| $25,000 | $35,000-$80,000 | 25% | $6,250 |

| $60,000 | Â | 18.33% | $11,000 |

In words, here’s how your income is broken down into tax brackets:

- You paid 10% of your first $10,000, earned in January and February

- You paid 15% of yout next $25,000, earned from March through July

- You paid 25% on your last $25,000, earned from August through December

In our example, you find yourself in the upper half of the 25% tax bracket at the end of the year but you’ve only paid 18.33% of your income in taxes – a full 6.67% lower then your current tax bracket if taken at face value. We like to call this the marginal tax bracket effect.

One interesting observation of the marginal tax bracket effect is that its effects get less noticable as your total income goes up. While our previous example paid 6.67% less then the 25% tax bracket’s face value, an individual at the top of the 28% tax bracket earning $170,000 per year will pay about 24.24% of their income in taxes – only 3.76% below face value:

| Dollars Earned | Tax Bracket | Tax Rate | Tax Paid |

| $10,000 | $0-$10,000 | 10% | $1,000 |

| $25,000 | $10,000-$35,000 | 15% | $3,750 |

| $45,000 | $35,000-$80,000 | 25% | $11,250 |

| $90,000 | $80,000-$170,000 | 28% | $25,200 |

| $170,000 | Â | 24.24% | $41,200 |

Why does the marginal tax bracket effect seem to diminish as you earn more? It’s a simple matter of rounding. The higher tax brackets are, by design, much wider then the lower brackets. For example, compare the $10,000 wide 10% bracket with the $90,000 wide 28% bracket. With more and more of your income falling into your highest tax bracket as your income goes up, the tax savings you get at the lower brackets become statistically less significant.

As you have seen in the previous examples, marginal tax brackets mean that the total percentage of income you pay in taxes is not the same as the face value of your highest tax bracket. While marginal brackets are somewhat more complicated to calculate then a simpler flat tax, they do come with benefits. Specifically, the marginal income tax system is designed to lower the overall tax burden on lower and middle-income taxpayers, while ensuring that taxpayers of all incomes pay the same marginal percentage in each respective bracket regardless of which bracket they fall in at the end of the year.

As the core of the American income tax system, understanding how marginal brackets work is a key step in understanding and taking control of your finances. Armed with this knowledge, you should be better prepared to make more informed tax and financial decisions in the future.

Footnotes:

How can we improve this page? We value your comments and suggestions!

How can we improve this page? We value your comments and suggestions! Send Instant Feedback About This Page

Donate BitCoin:

Donate BitCoin: